art review

correspondence 2

The visitors

Ernesto Bonato

They arrived in this world with curious eyes and hands eager to touch the earth, the ashes, the twigs they stepped on, the graphite mines. Their gestures were to scatter the seeds, to sow them in a spinning, half-crazy, half-drunken way. Their feet kneaded the mud, and the mud stained their bodies like blood, like their own flesh. They dug the soil with their nails until the humus ate their corn cobs while the damp smell of the beings that sleep in the shade rose and dilated their nostrils. They also planted the bones of their fellow creatures there, mixed with the seeds, the spores, the iridescent lichen. They ate the food, sucking and licking the juice that ran down their limbs, eagerly, happily, under the canopy of a huge ancient tree from which hung nests and shining webs. In the distance, the mountain ranges rose darkly against the light of the sunset. The fire, the blaze, was sought in fear, and with it they warmed their skins covered in intricate designs. Their whispers echoed in the depths of the forest like strange and threatening sounds. They lay down on gigantic leaves, imprinting their mixed up bodies, crushing the still living sap, which stained the earth. Huddling together, they opened their eyes towards the sky, with longing, remembering nebulae, gigantic jellyfish moving in distant space, and then they dreamed.

Ernesto Bonato

November 2024

correspondence 1

Landing Jumping Flying

Ernesto Bonato

Bristle soaked in the murky, black water. Blood of writing that runs through veins and fibres of the paper. The pen touches the pulp, cleaving worlds. Resplendent domes guard their darkness – Oriental cities.

The ink drips like the hours, like time, like the wet tears of an unwritten poem, but dreamt about in the half-open eyelids of a hawk against the blue sky. Memory and oblivion mingle in the spaces between the uncertain signs like the tracks of a crab in the fine white sand by the sea. Tracks-Words-Gestures. The drawing of a garden and of a flower that has dried. Images of faces evoked by affection (once more and more once), worn by the touches that caress them. Faint shapes, whispered by the wind that turns the pages of a notebook forgotten in the cool morning light. Abandonment. A high cornice, a transom. Imaginary calligraphies spun, interwoven by chance, made of carbon, fat and gum. Correspondence sent by the void, to the void. No time, no place.

Memory, desire, despair. The search for a happy life. In the vicinity of an immense tree, a house of concrete and steel shelters in its silences, vegetal palimpsests softened by the touch of the brush and the spirit, gathered by time and friendship. A transverse light touches their faces.

ATOTÔ! SILENCE!

Ernesto Bonato

August 2024

FLOWER AND STONE

Fernando Stickel

"Flower and stone. Light and dark. Hot and cold. Skin and bones. Red and blue."

Maria Villares’ work is extensive and enduring. Her pictorial universe is labyrinthine and inhabited by faceless beings. But they are there, silent, observing and commanding the show.

To get to know her paintings is like walking into a cave, holding a flashlight, discovering fascinating images that emerge from the darkness, sometimes using a magnifying glass, other times taking advantage of a banished ray of sun that is intruding into the darkness. You might also use a periscope, which will reveal some more surprising images… But what is this flower doing here???!!! This is what Maria Villares’ paintings are.

Maria does not seek the spotlight but rather the solidity of discipline, coherence and permanence. Her work uninterruptedly spans the years, one thing flowing into another, sometimes leaning towards engraving, sometimes towards ceramics, but always pointing towards drawing. Yes, drawing commands her destiny and her art, and this permanent truth shines through in this series of paintings made over more than two decades.

Maria’s paintings do not reveal themselves completely; they are discreetly generous in providing small clues to the active archaeologist who wants to delve into unknown spaces in search of flowers or other delicacies in the Garden of Earthly Delights of her work. Just like the luminous fish in the abyss, flowers grow in forbidden places…

Fernando Stickel

October 2023

WEAVING TIME

Luiz Armando Bagolin

"La durée est le progrès continu du présent qui ronge l’avenir et qui gonfle en avançant”

"Duration is the continuous progress of the present that gnaws at the future and moves forward”

Henri Bergson

At first, Maria Villares’ Nexus series may seem like a turning point, a self-imposed deviation from her career, which has been mainly based on drawing, engraving and painting. If in these forms the search revolves around the capacity that language has to still be at the service of representation (the masses of colour are surrounded by light and shadow, leading the images to organically recompose themselves in the abstract field), in Nexus, in addition to all this, the question of time is Maria’s main focus.

She works with the strategy, common to many artists since the 1960s, of serializing or developing ideas or themes through sets and subsets, duly titled, but there is a connecting bridge between them all: the understanding of time as an index of consciousness or intuited time, which dissolves the perception of space as a gathering of classifiable units conditioned by physical time.

Bergson called the latter the ‘t-variable’, spatialized time, which could be marked on a clock and which was the opposite of the inner time that referred to the past in the present, advancing incessantly towards the future. Unlike positivist time or the empirical sciences, Bergsonian time does not admit intervallic succession, gaps that develop linearly from the past to the future. The idea of progress is also relatively dissolved in it, with the different moments we live corresponding to perceived matters of the same time, which is always identical to itself and continuous in duration.

Indifferent to the ‘variable t’, Maria Villares has also produced a number of works over the years that interchange in terms of the question of presenting lived time, though their materials are varied, as are their results.

In addition to the series or simply understanding her work as homologous groupings of the various phases of her life, the intercourse of these occurs through a connecting channel, a link.

Nexus is therefore a kind of amalgam of the way in which Maria Villares produces and relates to her own work. But Nexus is also the name of a series that began in 2001, when she observed the spider webs wet with dew in the backlight of the morning, as she has stated. It is the moment of locating the universal in the particular, with the possibility of constructing metaphors about her memories: here again, time, seamless, passes through the past in the present, remembering the absence of the mother, and advances towards her future, representing the birth of one of her daughters.

Nexus links and comments on another earlier series, ‘Far beyond the Apple’. In some of the works in this series, the fruit is vivisected into very fine layers, minimally altering the seed tegument. The anatomy of the apple is simultaneously a plastic work, and the search for the origin of oneself in its genes and chromosomes is a metaphor for its own body and the woman’s body as a creative machine.

In Nexus, the series, the body is reconstructed through the interweaving of countless threads. Just as in the observation of the endocarp of the apple cut in half, the knots of the lines that intersect in these threads are transformed into gestural signs, a kind of signature or centres of macromolecules (chromosomes again?) that the drawing, monotype, engraving, rubbings and stitching reveal. But these are diaphanous bodies, boneless, soft or limp bodies which, as they gain space, depend more and more on the external environment to contribute to their final, albeit temporary, form or appearance.

From the sequence of flat images in which the bonds are represented as signifiers in graphic-pictorial spaces to the cocoons woven with nylon threads, Nexus seeks to be the synthesis of many past series and of incessant searches in the art environment, literally casting the duration of imagined time into space. It is from this time that the materials weave the spaces, whether large or small, it doesn’t matter, suitable for the process of artistic achievement.

Nexus is also currently an installation that appropriates the considerable internal space of the Biblioteca Brasiliana. Like Medusa, it extends tentacles in different directions, putting forward new ideas about the architectural apparatus designed by the organizing reason: its interstices and connections add up, gradually forming a gigantic and limp organism, similar to the ivy that advances over the ruined walls of the surrounding city. Tied to the space, these structures invite the spectator to interact, as in the works of Lígia Clark.

There is, however, a fundamental difference between this installation and the experiences derived from neoconcretism: here it is not a question of considering the perceptible object as something that will only be appropriated and experienced by the perceiving subject. The installed cocoon triggers all the other past experiences of the artist, perhaps also those of the viewers, making them participate in this invariable and continuous time. Thus, the work hanging in the space is not only there, in that place, but in many others, re-presenting itself, as affection, for example, in the thin nets that held her mother’s hair in the past. As a fruit of pure intuition, it coincides with the life of the Spirit, becoming yet another gesture that Maria had on that occasion.

Luiz Armando Bagolin

13 november 2019

MARIA WEAVING NEXUS

Ana Angélica Albano

"I only ever found the gift of sculpting dew in the spider”

Manoel de Barros

"The water droplets look like pearls hanging on the silk of the web after the dew has evaporated.”

Jiang Lei*

Maria Villares’ fascination with the pattern of spider webs sprinkled with morning dew resonates with the poetry of Manoel de Barros and introduces her to the craft of weaving: knitting waters that have passed by, she materializes emotions, she says.

The symbolism of the thread, present in many mythologies, is essentially that of the agent that connects all states of existence to each other and to the Principle. This symbolism is expressed above all in the Upanishads, where it is said that the thread (sutra) connects this world and the other world and all beings.

Maria symbolically retraces the path taken by so many women in ancient times, especially in China, where ritual weaving was associated with the weaving of the cosmos. In the silence of her studio, she invents her own rite of passage, materialized in works that allow us to contemplate the stages of her creative process.

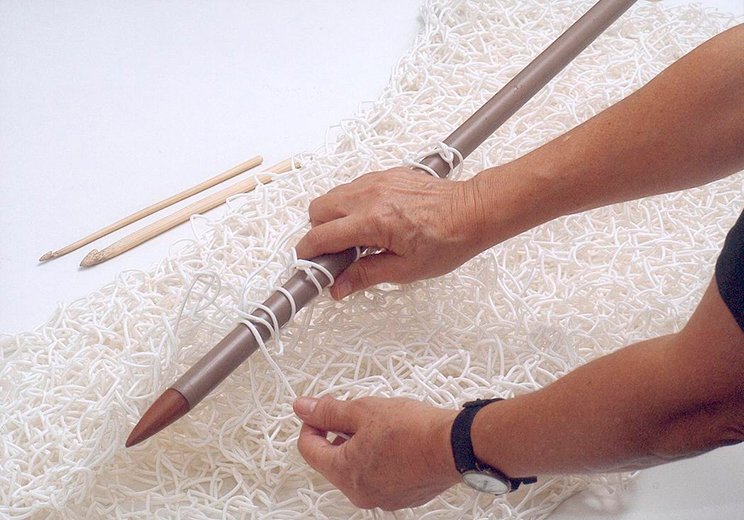

She begins by knitting an enormous web of luminous PVC threads and gradually entangling us in cocoons and rectangular modules. From weaving, she moves on to observational drawing and surprises us with drawings, in which she records, with obsessive precision, various phases of weaving. What was initially a record of the fabric gives way to a creative leap, and a multiplicity of graphic experiences begin to emerge.

Delicate drawings made with twigs, pens and brushes on small pieces of paper and also on very long pieces of paper. Some drawings are divided horizontally and are transformed into fragile objects protected by an acrylic dome. We can observe the continuous transition from weaving to drawing, painting, engraving and assemblage, in experiences that overlap, complement and renew themselves, without noticing the precedence of one over the other or the passage of time.

The luminous threads inspire other dark ones, as well as dense, dark drawings and paintings that gradually return us to the light again. With brushstrokes and coloured grooves, Maria lets us glimpse the gold of the alchemical process of transforming memory into invention: work.

Ana Angélica Albano

summer 2018

* Jiang Lei, scientist at the Beijing National Laboratory, where researchers have been studying how the silk of the spider is able to trap morning dew.

CLUES

Luciana Eloy

The Pistas [Clues] exhibition at Espaço Nexus brings together different moments in the creative journeys of the artists who are part of Ponte Cultura [Culture Bridge]. Everything is connected by the artists’ notebooks in the most diverse media and formats, in addition to other objects that are shown here as indexes and traces of the constructive gestures that permeate the process of these poetic elaborations.

The works presented here reflect a little of each artist’s perspective on the world and how they have followed different paths, expressing their ways of developing their creations. It is possible to see how these paths have been formed in terms of connecting ideas, recording thoughts, following paths, collecting materials. Actions that move towards highlighting marks of lived experiences that are gradually transformed into something unique.

Mixed in with these manifestations we can find clippings of times and spaces, lines that draw cartographies of affections, bonds with nature, with everyday life, with the earth and the body. Aspects that in some way are threads that weave the poetics of these artists, which here give clues of what could become future work, a new organization of reality.

Highlighting these process clues of processes in an exhibition is an important moment for Ponte Cultura, which has been working with the concept of new crossings since March 2016. Understanding crossing as a path that we cross together, between territorial and emotional borders, always seeking to stimulate practices in a circuit of artists from different cultures and perspectives.

Ponte Cultura thus operates on the path of bringing differences closer together, blurring the boundaries between nationalities, ways of thinking and artistic practices, allowing these experiences to encounter the public and thus provoke new perceptions and new perspectives on the world.

Luciana Eloy

22 March 2017

SO NEAR, SO FAR

Ana Angélica Albano

In the beginning, there was engraving and five artists searching for their landscapes.

United by love of their craft, they exchange secrets, revealing paths without, however, mixing their images which, despite the intimacy that gradually develops within the group, remain their own.

When I am invited to enter the intimacy of their studios, with each door that opens, I see the originality of their processes, the delicate power of such distinct poetic paths. And I accept the challenge (and the privilege) of accompanying them in the creation of an exhibition.

With each visit, I see mountains, islands, deep waters, unreachable horizons, a beach house, tiny trees, large unkempt trees, clouds laden with storms that never come, a waterfall, a pot, dreamlike foliage, threads, roses that reveal a woman’s face, the outline of a hand… Images that carry desires, dreams, mysteries. Silent stories presented, but not revealed, in the images transformed into engravings in the solitude of the studios.

The engravings, by decision of the group, are all printed on paper of the same size and have landscape as their theme. The format and theme, however, are only the pretext for a collective project, which each artist carries out in their own way.

Matisse, quoting Delacroix, wrote: having made the necessary studies to begin a painting, it is necessary to get to work and exclaim: “And now, to hell with the mistakes!” He then added: it is necessary to let intuition speak.

Allowing myself to be guided by intuition, I sought to carefully observe the intuition that had guided each artist’s path. And, in the selection of works, I opted for the unveiling of processes, for the (apparent) repetition of images that contain subtle differences, also including what might be considered errors but which contain the strangeness necessary for the emergence of poetry.

The intention is to put the viewer in touch with the thinking of each artist, making them an accomplice to their poetics.

An invitation to enjoy a time of delicacy… so close, yet so far away.

Ana Angélica Albano

summer 2017

NATURE, THE SENSES AND THE WORK

Rosely Nakagawa

Throughout Maria Villares’ artistic production, we find a keen eye for nature; seeds, shells, skins, found, gathered, noted and placed in collections. The gaze that focuses on the search for these elements is united with that which constructs the work.

Each work shows the evolution of a process that strengthens the relationship between specific techniques (painting, ceramics, engraving or drawing), transforming the residue of nature into a basis for constructive thought.

The sheets of paper are treated as shells that cover the base of the painting.

The pigment is dragged by water over the paper, weaving transparent skins.

In the painting, the layers of paint dissolve into white veils; the colour applied to the forms weaves webs, organs, bones.

In ceramics and bronze, the seeds gain a territory to be fertilized, building organic forms, bringing living matter back to the clay.

The referent reappears and disappears in layers and forms that approach and move away.

Abstraction, always accompanied by a strong relationship with matter, arises from its pictorial and formal strength.

Rosely Nakagawa, 2015

for the Maria Villares Exhibition – Inauguration of Espaço Nexus

Espaço Nexus – São Paulo, SP

BETWEEN US

Margot Delgado and Maria Villares celebrate yet another encounter in this exhibition, to which gave the contented title of Entre nós [Between Us]. It is a celebration of a friendship built on the complicity of affection and craft. Margot and Maria also share their neighbourhood with the trees of the São Paulo district of Alto da Boa Vista. And when a flower falls from the magnolia grandiflora in Margot’s garden, she gathers it in drawings or takes it to Maria. It is not a dead thing to be shared, but it is in transformation, whose temporary vigour is gradually transformed into perennial dryness. As the flower loses its fluids, it becomes another material, with new colours and shapes. And, not infrequently, it also feeds her friend’s work. In Maria’s studio, she joins the sambaquis made of shells, stones and driftwood, others stored that contain other stories. This exhibition features two distinct poetic projects side by side, but they have in common this attentive look at the changing states of being.

Origin

Maria Villares has always had a particularly attentive eye for the forms of nature. She recalls that observational drawing played an important role in her learning.

For some years now, Maria has been interested in the internal metabolism of plants and minerals and especially in the decay caused by time – the flower that withers, the apple slices that oxidize, the shells that lose their colour, the eggs and twigs that age. Paradoxically, and because this was not a linear process, embryo and death were confused. The cupboards and drawers of her studio, filled with this collection of susceptible models which are always at her disposal, form a curious cabinet of wonders.

From the observation of these dry lives, she has produced works in various techniques and languages. Paintings depicting skeletons, ceramics that mimic small bones, stones and sculptures, engravings, drawings, small cutouts and collages, mixed techniques have all emerged. It is surprising to see that in the last three years she has left aside, at least temporarily, the theme of decay. Her collection of specimens continues to inspire her, but the tension of her previous work gives way to relaxed forms that breathe freely on the vastness of the paper. Even when she leans over a dry orchid branch, it is to celebrate beauty, in a poetic series of three “Japanese” watercolours that recall the language of sumiê.

She has recently been working with lithographs, and some of them receive interference, where the graphic style predominates. This exhibition features some of these examples, in which black and colour coexist, sometimes on elements of architectural observation. Also shown here is a set of watercolours and mixed media, smaller in size and intense in colour, made in 2005, in which one can glimpse a flower, a vase, but what really matters is the wisdom in the construction of the masses of colour and the material resulting from the combination with other techniques, such as oil sticks, charcoal, or overlapping layers of acrylic paint, creating glazes.

This is the case of the only large work in black and white. Her natural eloquence is no longer entangled in the themes of death or emotional imprisonment. Maria seems to have exorcised the knots and threads with which she produced objects and engravings that made up the Nexus series in order to surrender herself to the adventure of these magnificent watercolours. The vehemence is now in the broad gestures, in the expressive graphics, in the flowers that are not afraid of seduction, half-open against the receptive and clear background of the canvas. These watercolours originally represent flowers, but they are rich in other suggestions – sometimes a bird, other times people or objects.

And there is also, quite simply, the pleasure of the broad gesture, the fortune of grandiloquent and wordless writing. It is not only the artist’s hands that work, accustomed to facing the skills of the crafts, but a whole bodily choreography can be guessed. In truth, the emerging theme is that of freedom, and Maria seems very comfortable on this new path.

Vera d’Horta, March 2015

MARIA`S NEXUSES

Manufacturing existence and its limits have always interested Maria Villares. She has observed the internal metabolism of forms, seeking to understand marginal processes. The skeleton of natural beings, visible in X-rays, the form of driftwood picked up on the beach, the radiating structure of a spider’s web, all of this has suggested paths to follow.

When she dissected the apple into slices, it was to closely follow its death, the loss of fluids,to examine the residues, the dry skins becoming shields. Then she realized that its halves bore clear embryonic suggestions, life presenting itself again. Seeds, cocoons, fetuses are references to a uterine nature that have inhabited her works for some time. In the ceramic piece in this exhibition, the stone in the middle of the water unites the mimesis of gestation with the delicate suggestion of ikebana.

In more recent works, she continues to X-ray this construction of meanings. The process is the same as that followed by those who have words before ideas. And it is the words that intertwine to construct a meaning whose origin no one knows exactly. The ancient and eternal feminine gesture of weaving and enveloping, protecting and meshing, is amplified in these works. Large needles and the repeated movement of hands constructed, together with white plastic threads, meshes that are not meant to be worn.

When the work grew, its weight on her womb brought her to tears. A meaning was born. She lived the interior of this process focused on the cadenced rhythm of her fingers, like Penelope, who made an alliance with the infinite time of waiting. It is not by chance that Maria gave this series the name Nexus, and the genealogy of the term is revealing. In Latin, nexus is a knot, a loop. Hence, connection, bond, union.

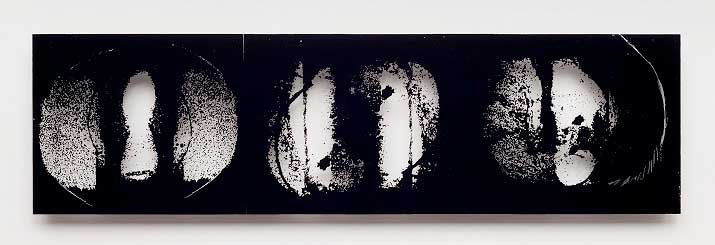

The group of knots constructs the web, which is presented as a loose body, but which is also a layer, an armour that breathes. The result is rarefied and solitary structures, of imperfect construction, which display all the accidents of their manufacture. Half knitting, half web, their hollow bodies cast shadows in space, and these projections are like moving engravings. It seems almost natural that the threads would then move onto the surface of the paper, first in the form of a drawing, then as engraving.

The ink strokes rewrite, with contained drama, the plot of these silent agonies, and the back and forth of the loops results in a sort of mirrored writing. The apparent scribbles of the drawings fray the threads, create vortices, and open spaces for light. In the engraving, positive and negative are mirrored again, unfolding their images.

And in these enlarged sequences, what matters less is perfection but rather the affective mapping of the fabric and the process. And it is worth remembering Aristotle when he said that manual crafts complete what nature did not finish.

Vera d’Horta, 2006

for the Exhibition Maria Villares and Margot Delgado

Galeria Gravura Brasileira – São Paulo/SP

MARIA VILLARES: THE EPIPHANY OF LIGHT

Margarida Sant’Anna

For some artists, the white of the canvas or paper can inhibit the creative act; for others, it can be the passive medium for expression: the resistance of the material and the white as a colour or luminous field seem secondary. In Maria Villares’ recent work, the white resists: light and surface are conquests. For Maria, the experience with the world is a form of knowledge, hence the confrontation with the medium of the work and the search for luminosity. There are no “a prioris” in this work: the possibility of a poetics appears only later, once the plane has been constructed and emphasized. Then, from the materiality of the two-dimensional character emerges the web of chromatic and compositional relations based on the attempt to order the sensitive world, which occurs through the reduction of elements of the representational nature.

There is something ethical in this work, in this gesture reflected in the experience of reading things beyond their appearance. A synthesis that asks the gaze to have a different perceptive time — the time of contemplation — while also proposing a different experience for the gaze that swallows up the visual appeals of the contemporary world. And indeed, what at first glance seems like a modernist praise of the plane hides something that only the slowness of perception can reveal. From the patient repetition of the gesture, like a craftsman smoothing a surface, from the successive superimpositions of matter, resulting in subtle tonal variations, the light gains strength.

The artist rarely appropriates inscriptions written in the London urban landscape, the starting point for one of the series in the exhibition. One of them, however, surprises by its coincidence (if coincidence exists) — “godard” — and here, the circle seems to close: in Passion, before the white “screen”, Godard (the director) inquires about the (im)possibility of creation. Maria Villares responds empirically to this impasse. The meaning of these works is precisely the possibility of artistic creation in direct relation with the world.

Margarida Sant’Anna, August 2001

Solo Exhibition – Papéis [Sheets of Paper]: 1998-2001

Galeria Nara Roesler – São Paulo/SP

BEYOND THE PLEASURE PRINCIPLE

Maria Alice Milliet

"Sublimation is a search in the outside world for the lost body of childhood"

Norman O. Brown

The body mobilizes artistic creation. There is a trend in contemporary art that finds its roots in the psychic life structured from bodily experiences. Unconscious fantasies generated in early childhood make up the subliminal plot of these representations. Secret stories of love and hate, primarily involving the mother, then the father when the classic child-mother-father triangle is formed, resurface in these works. Mother and father rarely appear in their entirety, victims of a recurring metonymic operation that makes body parts – breast, mouth, genitals, womb, viscera, excrement, etc. – targets of childhood desire. These objects of affection or repulsion can be replaced by others to which they are somehow associated such as the uterus, the seed, the shell, the house, the box, and so on. The child projects contradictory feelings, loving and/or aggressive, onto each of them. This pattern of interaction that is always in crisis results in the ambiguity of the signifiers it inspires. Identities are created, emotions are transferred, correspondences are established without any respect for conventions. In the realm of fantasy and art, anything goes.

The scope of this artistic production goes far beyond narcissistic daydreaming. It deals with experiences prior to verbalization that continue to be reinforced or diminished by events after early childhood; in short, a subjectivity whose existence inevitably depends on the other, hence its anguish, pleasure and pain. The immersion in the universe of the child and the family – the matrix of all socialization – finds its greatest expression in Louise Bourgeois. It is impossible not to recognize in her objects and installations the drama she stages. In the transposition of the familiar to the symbolic, from the anecdotal to the mythical, one constant imposes itself: the conflictual relationship.

When Maria Villares begins to work on the apple, the deep contents that motivated her were not evident. Looking back, one can perceive the presence of the archaic in earlier works, especially in the enormous drawings from 1994 that were made from the register of twigs and driftwood collected from the seashore and then converted into totemic beings floating in an unreferenced, timeless space. Even earlier, shells, snails and corals appeared in glass boxes that she calls aquariums. In this case, it was the organic world observed in vitro, the same distanced stance that Maria takes on when she is initially dealing with the apple. For a long time, the discipline of science prevails. She selects and submits the apples to a series of operations, gathering information about their different states. She observes the whole fruit or in thin slices placed on sheets of paper like slides in a laboratory; she notes the transformations of the material, that is, the changes in colour, the stains on the paper, the wrinkling of the skin, the reduction of the pulp, the hardening, the mummification. She then proceeds to a series of experiments, taking photographs and photocopies of this material, interfering with the records and reproducing them in successive operations.

This “objective” approach gives the first series of works a pseudoscientific quality. However, despite the great concern with formal and technical control, the playful aspect emerges. This is when she discovers that sliced apples printed on transparent acetate, when superimposed, allow for compositional games. This leads to manipulable objects. On the other hand, the cuts seen in transparency make one think of X-rays of the human body. Knowing the innside of the body has always been fascinating. Rummaging through what has been stored, Maria finds X-rays of internal organs that she places on the studio window, backlit. At the same time, she has been making erotic drawings. Nothing explicit, rather the topological apprehension of erotic sensation, continually shifting from one region of the body to another. The quality of these drawings reveals a mature sensitivity. However, the graphic form, perhaps because it is already very refined, is not enough for her.

Maria, who had reduced the volume of the apple to two dimensions by cutting it, suddenly returns to three dimensions. The creative process, which had been well-behaved until then, now shows a boldness, I would even say a shamelessness. The apple takes shape, becoming a semi-spherical object on the wall, in the centre of which there is a translucent button: a large, fleshy, swollen breast/apple, frightening in its gigantism. It is worth remembering the childhood fantasies in which the baby, who finds its greatest satisfaction in the breast, also has aggressive impulses towards its object of pleasure. Out of frustration and fear of loss, the child dreams of sucking, biting, devouring the breast, ultimately possessing the mother whose omnipotence becomes oppressive. Marcel Duchamp, always a pioneer, had already isolated the breast in his 1947 work Prière de toucher.

The cruciform object made up of five coupled segments constitutes an even more surprising development of the work. “Estive aqui” [“I was here”] is the suggestive title that Maria gives to the work. The Kleinian model, which has the unconscious fantasy as the principle of structuring social life, is also part of the reading of this play where the apple – the forbidden fruit – is confused with the uterus – the place of gestation – in shape and colour. The soft, upholstered red fabric of which the cross is made gives the Christian symbol carnality. The obscenity of this representation lies in combining the idea of sacrifice with the triumph of the flesh.

Finally, the flag has an apple cut in half printed in the centre and on it the inscription taken from Genesis: “For God knows that when you eat from it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.” The banner cut into strips allows one to pass through. The Passage, symbolically a violation, is the access route to knowledge as stated in the biblical sentence. Despite the aggressive impulses implicit in these works, one cannot ignore that there is something of pop irreverence in them. The gigantic version of real objects, the stuffed volumes, the bright colours bring to mind the soft sculptures of Claes Oldemburg. Transiting from the edible to the erotic, from the banal to the symbolic, from the apple to the breast, to the cross, to the bar curtain, Maria incorporates humour into her work, an indispensable ingredient for the balance of this artistic equation.

Maria Alice Milliet

14 July 1999.

Solo Exhibition – Muito além da maçã [A long way beyond the apple]

Galeria Nara Roesler – São Paulo/SP

THE TRANSFINITE UNIVERSES OF THE APPLE

Norval Baitello Junior

The Other Side of the Forbidden Fruit

One day, Maria Villares drew an apple. And, as she drew, she discovered, in the entrails of the fruit, the anatomy of the great myth, the main founding myth of Western culture, but not only in its superficial version of the forbidden fruit of the Garden of Eden. She uncovered, in the entrails of the apple, the homologies between the world and the womb, that is, between heaven and ecstasy. And, as in every myth there is an origin, so too in the fruit there is sometimes a fetus, sometimes a photo, sometimes a fact, all waiting to be discovered, to be revealed. A fetus, a photo and a fact always point to the unveiling of a secret, the unfolding, the opening out, the development of a possibility, the blossoming of a new form. They are always open narratives. Just like the anatomy of the apple, by Maria Villares, a narrative pointing to open possibilities.

The Transfinites at the Heart of the Apple

And the apple becomes a theme, a motif and a character, which all unfold in infinite variations and show infinite facets. Like Jorge Luis Borges’ Aleph, infinity is not external, but internal. As in the mathematics of transfinite numbers, the apple contains a world in its core, in its most intimate and unfathomable soul. The essence of symbols – such as the symbol ‘apple’ – and their destiny are none other than this: to be a part that contemplates the whole, to be the point that contains the universe, to be the insignificant that shelters infinity. (Just as the fate of the seed, or, equally, that of the uterine space, is none other: to contain the new being, in embryo). And to understand this mythical mathematics of the infinite within the finite, Maria Villares has been experimenting with the apple and its developments: cutting, slicing, drying, leaving it to the worms of decomposition or preserving it with formalin, following its wrinkling skin, photographing its changing configurations, observing its juices of decomposition and, above all, producing unconventional records based on the apple and her drawings. These records unfold in many series, using diverse mediums, materials and techniques: sketches and studies on paper, apples laminated on acetate, monotypes, and drawings on tracing paper, boxes, transparencies. Everything unfolds into a new face of the apple, transfinitely.

The Movements of the Apple

Her attention as a naturalist observer, however, is no greater than her ability to generate metaphorical superpositions, unfolding her object in infinite series of mythical, cultural, and historical associations, seeking deep meanings for the phenomena of nature. Thus, the series of transparencies are born, the result of photographs of slices of apples. These are photos that sometimes transfigure into fetuses, always accompanied by traces, redrawn, in their arc movement, of a curved spine. Sometimes the transparencies are themselves the exposing of the apple’s innermost being, sometimes they are pretexts for an even deeper exposition of the facts that the apple has come to symbolize, the uterus and its fruit, ecstasy and, in turn, its imperiousness. The movement of the apple is always concentric, like everything transfinite: infinity turned in on itself and its core.

Fire, Breath and Sensuality

The movement of concentricity, present in the longitudinal or transversal cuts and slits, pointing to fertility, the seed, the foetus, brings back the principle of life. In Western myths of creation, breath represents the primordial gesture. Maria Villares twists copper wires into fetal movements, over them the sensitive rice paper, or else selects various slides of different cross-sections of the fruit under this paper, and finally applies blows of hot air, leaving on the paper the record of the breath, the fire and the sensuality, of the apple and its movements, its spaces and its entrails. The result is the record of ecstasy as the primordial gesture of creation. The transfinite apple, the object of Maria Villares’ art, allows us to glimpse a sensual God who whispers his hot breath over the seeds, transforming them into creatures.

Norval Baitelo Junior

16 August 1998.

MARIA VILLARES

Maria Alice Milliet

Maria presents her first solo exhibition: an explicit confrontation between the chromatic exuberance of painting and the severity of drawing.

The complete mastery of expressive means derives from a silent obstinacy and attests to the maturity of her work. There is no gratuitousness or spontaneity in the creation; the artistic quality of the whole is based on the profound knowledge of traditional techniques into which Maria incorporates resources acquired through experimentation. There is impetus and restraint, lyricism and drama in the exercise of “faithful efforts and provoked surprises” (Bachelard).

Maria’s poetics always involves the drama of matter as resistance and transformation. Her creation is part of the friction between being and becoming.

During her daughters’ childhoods, she began working in ceramics, making utilitarian objects until the exploration of the sculptural form took hold. An imaginary botany made from the invocation of seeds and shells is configured in sculptures where ceramic and bronze are associated. Capsules in which the enamelled clay cores are enveloped by rough metal. It is the diminutive that becomes gigantic, free from established grandeur.

The transition from ceramics to watercolour took place after a period of intense restlessness. In an improvised studio without natural light, Maria devoted herself to drawing with charcoal and graphite, then moving to a larger space and the irruption of colour into her work.

And we arrive at the dry aquarium, a source of artistic inspiration, a place where the images of her later works are metabolized. In glass containers Maria collected souvenirs from the beaches she has visited: shells, snails, pebbles, driftwood, fragments of rock… There she retained the charm of the strangeness of shapes and colours, produced by the wear and tear of water and wind on the objects collected. Here we are before an archaic beauty.

The contemplation of this microcosm initially resulted in watercolours and then paintings on canvas. In the works on paper, watercolour stains form subtly articulated compositions with the linear thread. On the canvases, in an initial phase, the watery, the translucent temperament of watercolour persists. Once the transposition to the new technique is complete, the field expands, and the oil imposes its character. The pictorial mass gains density through the superposition of layers or when the paint is thickened with other materials. The colour moves through the chromatic scale and reaches saturation. The line, resulting from an unhesitating gesture, energizes the canvas. In her current production, painting asserts its autonomy: in the materiality – paint and canvas – resides the substance of its own becoming.

On a trip to the state of Maranhão, Maria collected pieces of wood left stranded by the tide. In a series of small drawings, she attempted to apprehend these fragments corroded by salt water, grazed by sand, lashed by wind. This aggressive action had left marks and encountered resistance. Protrusions and recesses were inscribes on the once smooth surfaces, transforming the volumes into tortured forms: an entire history had been recorded in these bodies.

Returning to São Paulo, Maria transferred some of these notes to large dimensions on paper, canvas or polyester. A new phase of her work began.

The debris took on the appearance of ancestral entities dramatically treated in black, white and shades of grey. They floated like meteorites. Alone or in pairs, they emerged ghostly from empty space, slowly approaching or at the centre of a whirlwind of light.

Maria Alice Milliet

September 1994

Solo Exhibition – Maria Villares

Galeria Nara Roesler – São Paulo/SP